A Preventable Crisis: How Unrecognized Constipation Led to a Life-Threatening Emergency for a Person with IDD

A Preventable Crisis: How Unrecognized Constipation Led to a Life-Threatening Emergency for a Person with IDD

For people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), routine health issues can quickly spiral into dangerous medical emergencies when early warning signs are overlooked. One such condition is severe constipation, which is often dismissed as a minor inconvenience but can lead to serious complications, including bowel obstruction, vomiting, aspiration, and even sepsis.

Constipation is a common issue among people with disabilities due to factors such as medication side effects, reduced mobility, and dehydration. When left untreated, it can progress to a life-threatening situation—one that is entirely preventable with proper awareness and intervention. The following case is based on real-life events.

Emma’s Story: When Simple Symptoms Turn Dangerous

Emma, a 46-year-old woman with cerebral palsy and an intellectual disability, lived in a residential care home where she received daily support with meals, medications, and hygiene. Due to her limited mobility and the side effects of certain drugs, she was prone to constipation, a condition that required careful management through hydration, fiber intake, and regular monitoring of bowel function.

Over the course of several days, Emma’s supporters noticed she had stopped having regular bowel movements. She also lost interest in food and appeared more fatigued than usual. Rather than recognizing this as a sign of worsening constipation, staff assumed she was simply not hungry.

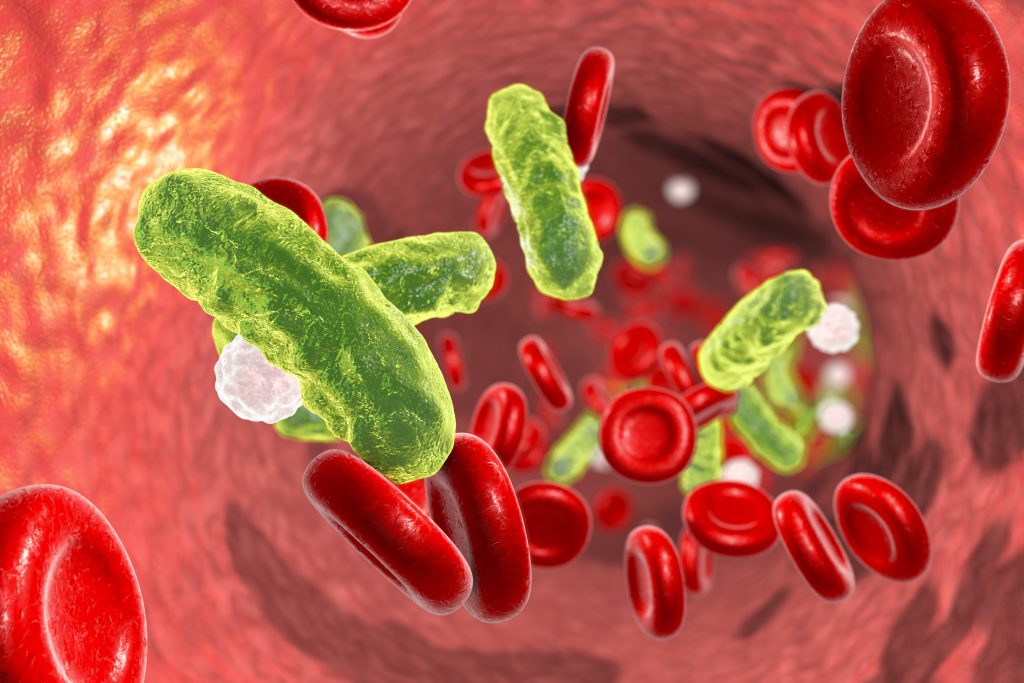

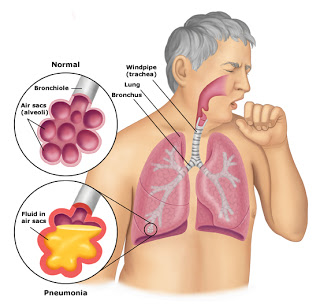

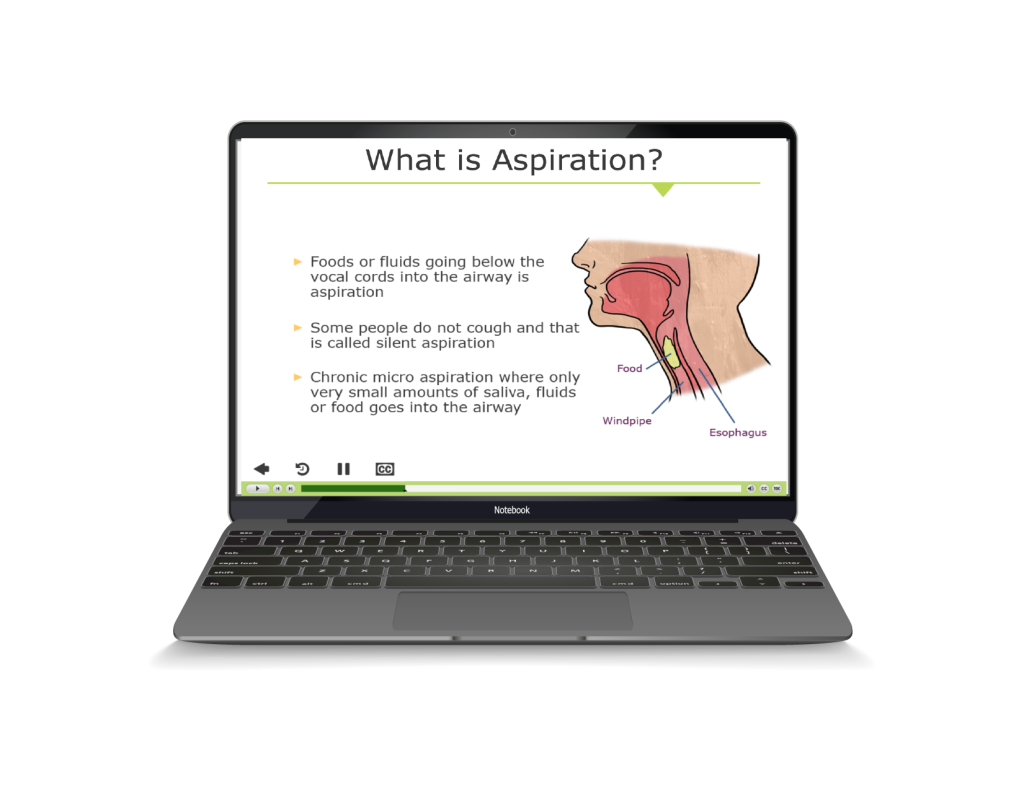

As her condition deteriorated, Emma began vomiting—a red flag indicating a possible bowel obstruction. Unfortunately, she vomited and aspirated some of the material into her lungs, leading to aspiration pneumonia, a serious infection that made it difficult for her to breathe. By the time she was rushed to the hospital, she was in respiratory distress and required immediate intervention.

The Cost of Delayed Action

Emma’s hospitalization and recovery were both lengthy and costly. She spent:

- Five days in the intensive care unit (ICU), receiving oxygen therapy and antibiotics for aspiration pneumonia.

- Another two weeks in the hospital, recovering from the obstruction and pneumonia.

- Several weeks in rehabilitation to regain her strength and relearn how to eat safely.

The total medical costs exceeded $350,000, not including the emotional and physical toll this crisis took on Emma, her family, and her supporters. The heartbreaking reality? This could have been avoided entirely with early recognition and intervention.

How IntellectAbility’s Tools and Training Could Have Prevented Emma’s Crisis

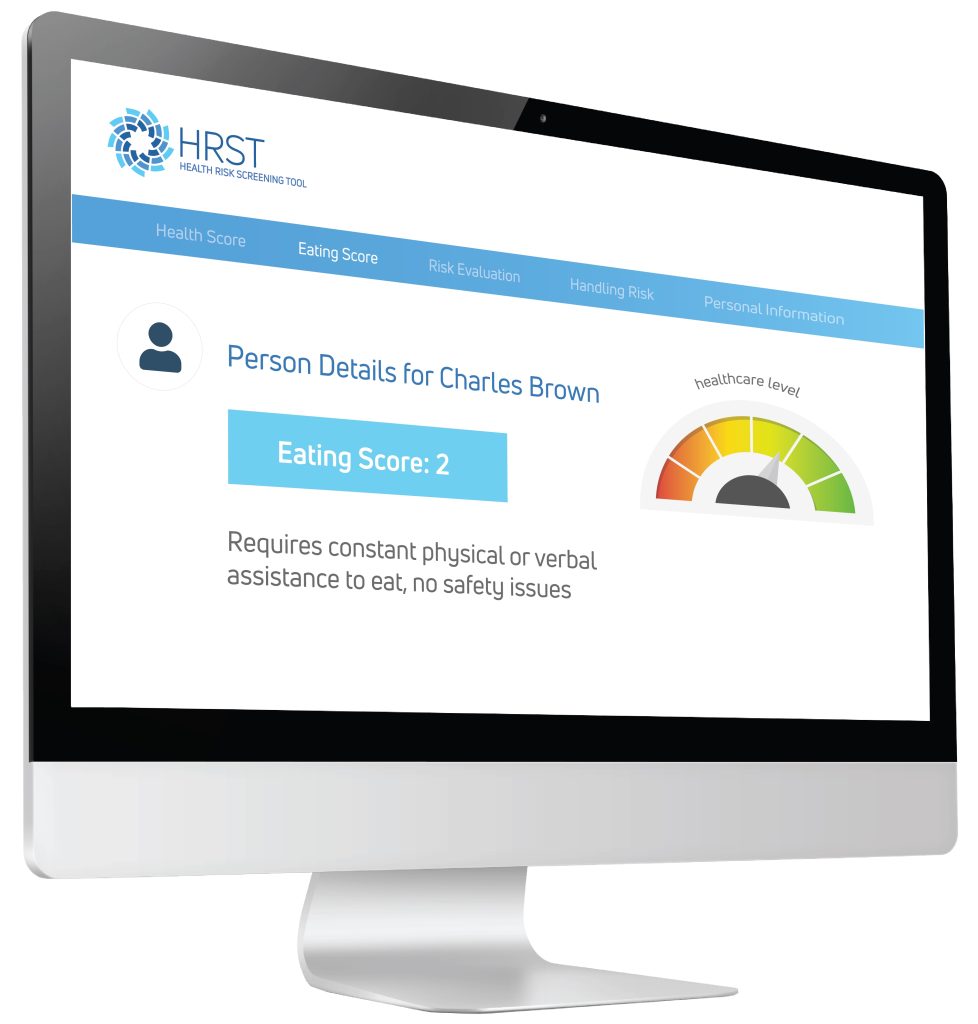

Constipation is not a minor issue—it is a serious medical risk that requires proactive monitoring and management, especially for people with disabilities. IntellectAbility’s Health Risk Screening Tool (HRST) and specialized eLearning training programs provide early detection strategies that can prevent emergencies like Emma’s.

- Health Risk Screening Tool (HRST): Identifying Risks Before They Escalate

The HRST is a scientifically validated tool that helps support teams recognize medical vulnerabilities early. If Emma’s supporters had used this tool:

- Her history of medication-induced constipation and reduced mobility would have flagged her as high-risk for bowel obstruction.

- A more detailed care plan could have been implemented to increase hydration, monitor bowel movements, and intervene at the first signs of constipation.

- Supporters would have been more thoroughly trained to identify subtle warning signs, such as decreased appetite and fatigue, as potential indicators of a serious underlying problem.

- Supporter Training: Recognizing and Responding to Early Symptoms

One of the biggest reasons Emma’s condition became life-threatening was a lack of understanding about the dangers of constipation. IntellectAbility’s training programs ensure supporters can:

- Recognize early warning signs of constipation, including appetite loss, abdominal discomfort, and behavioral changes.

- Take action before a crisis occurs—such as increasing fluids, consulting with a pharmacist about medication side effects, and seeking medical advice if symptoms persist.

- Understand the link between vomiting and aspiration pneumonia and respond immediately to prevent respiratory complications.

- A Person-Centered, Preventive Approach to Care

IntellectAbility’s approach focuses on prevention rather than crisis response. By empowering supporters with the right tools and knowledge, individuals with disabilities receive consistent, high-quality support that reduces avoidable hospitalizations and improves overall well-being.

Why Do Preventable Cases Like Emma’s Still Happen?

Despite how common constipation is among individuals with IDD, many cases go unrecognized until they become critical. The reasons include:

- Supporters misunderstanding the severity of chronic constipation

- Lack of routine health monitoring to track bowel movements and digestive health

- Failure to recognize appetite loss, vomiting, and fatigue as early signs of a medical emergency

Constipation should never lead to hospitalization—yet cases like Emma’s continue to happen due to delayed intervention and lack of awareness.

The Solution: Prioritizing Prevention Over Emergency Response

Emma’s hospitalization was entirely avoidable. With routine screening, proactive health management, and caregiver education, her supporters could have recognized and treated her constipation before it became life-threatening.

Using tools like the HRST leads to:

- Earlier detection of digestive health issues

- Fewer emergency hospitalizations due to complications like bowel obstruction and aspiration pneumonia

- Better-trained supporters who can confidently identify and manage medical risks

Constipation should never be dismissed as minor—for people with disabilities, it can be a gateway to life-threatening complications if left untreated. Emma’s story serves as a critical reminder that small warning signs should never be ignored.

By implementing IntellectAbility’s low-cost, high-value Health Risk Screening Tool and evidence-based training programs, we can ensure that people with disabilities receive proactive, life-saving care, reducing unnecessary suffering, preventing medical emergencies, and improving long-term health outcomes.

The solution is simple: Act early. Educate supporters. Prevent unnecessary hospitalizations.

The real question isn’t whether we can afford to prioritize preventive care—it’s whether we can afford not to.

Health-related Resources for People with IDD and Their Supporters

Health-related Resources for People with IDD and Their Supporters With significant health disparities noted in people with IDD, it is important that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), their supporters, and healthcare providers educate themselves on the different health risks that are more commonly seen in people with IDD and about what can be done to prevent serious complications. Supporters and healthcare providers are often challenged in finding helpful information related to healthcare for people with IDD. As a physician who started practicing in this field in the 1990s, finding clinically relevant information about healthcare for people with IDD was challenging. Fortunately, over the past several years, more resources have been developed that relate specifically to healthcare issues and improving health equity for people with IDD. In this article, you’ll find a listing of websites, tools, and training available to provide information and guidance to you, whether a family member, paid supporter, healthcare provider, or person with IDD.

With significant health disparities noted in people with IDD, it is important that people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), their supporters, and healthcare providers educate themselves on the different health risks that are more commonly seen in people with IDD and about what can be done to prevent serious complications. Supporters and healthcare providers are often challenged in finding helpful information related to healthcare for people with IDD. As a physician who started practicing in this field in the 1990s, finding clinically relevant information about healthcare for people with IDD was challenging. Fortunately, over the past several years, more resources have been developed that relate specifically to healthcare issues and improving health equity for people with IDD. In this article, you’ll find a listing of websites, tools, and training available to provide information and guidance to you, whether a family member, paid supporter, healthcare provider, or person with IDD.

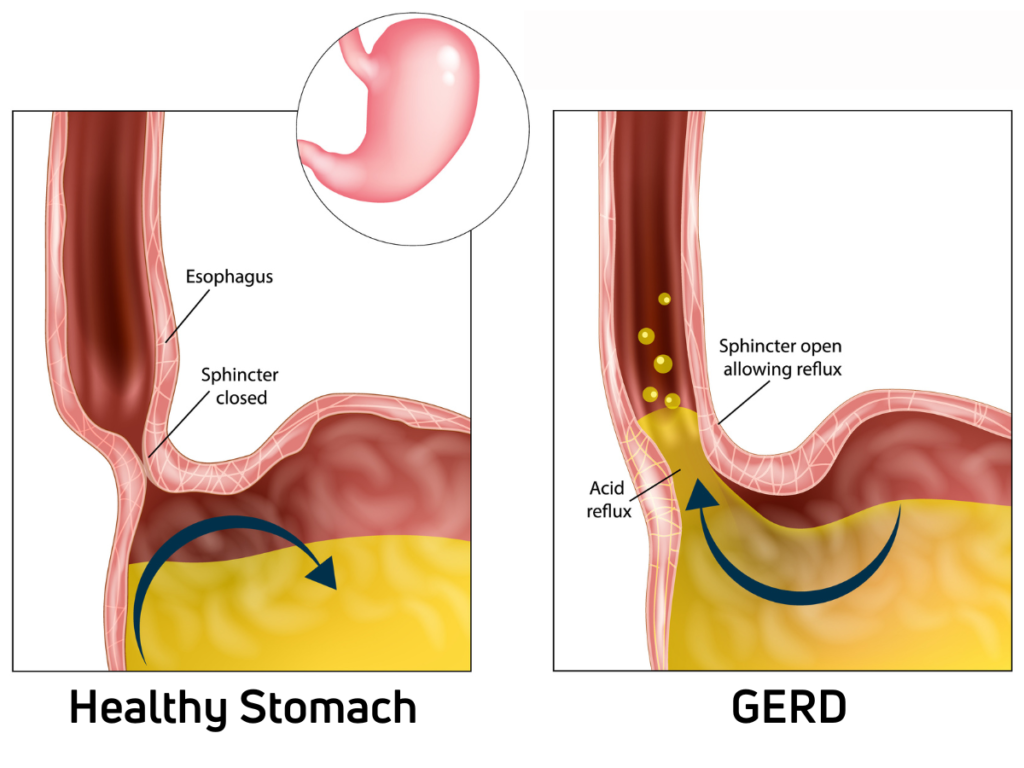

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).