Unlocking Behaviors: Psychiatric Symptoms

Unlocking Behaviors: Psychiatric Symptoms

Co-written by Risley “Ley” Linder, MA, MED, BCBA & Craig Escudé, MD, FAAFP, FAADM

This article is part of a co-authored series on behavioral presentations in which a physician and a behavior analyst provide insight into real-life case studies to share their expertise on how cogntivie changes can be addressed in an interdisciplinary fashion.

Jerome is a 23-year-old man with a mild intellectual disability who is a proficient verbal communicator, both expressively and receptively. He is a reliable historian and self-reporter who easily conveys his wants and needs. Jerome has no known medical issues but has diagnoses of psychosis and depression for which he currently takes aripiprazole and mirtazapine. He works washing vehicles for the agency where he resides and enjoys playing basketball at the local community center.

Jerome moved to his current home approximately six months ago, where he resides with three other men close to his age who have similar social and adaptive skills. Over the last four to six weeks, staff members have noted that Jerome has begun refusing to attend work and is not going to the community center. What was once ordinary and occasional frustrations with housemates have now turned to yelling and cursing, slamming doors, and walking away from his home.

When speaking with Jerome, he is having difficulty focusing and is fidgety. He self-reports that he is sleeping poorly, “needs anger management,” and is “sick of these people bothering me.” When asked about a recent incident with his housemate that resulted in a physical altercation and law enforcement involvement, Jerome immediately becomes agitated and begins pacing, cursing, and making threats to harm people. Further discussion with the staff has noted that Jerome has been upset for several days and has intense emotional reactions to innocuous social interactions and general task requests.

Medical Discussion

Upon the first review of Jerome’s situation, it seems that these changes he is exhibiting are likely due to environmental and/or psychological conditions. However, because there are so many underlying medical conditions that can cause behavioral changes in people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), we must always look at the possibility of some treatable medical cause. Even though Jerome is noted to be a good communicator, a person may have difficulty expressing changes in their body, including discomfort.

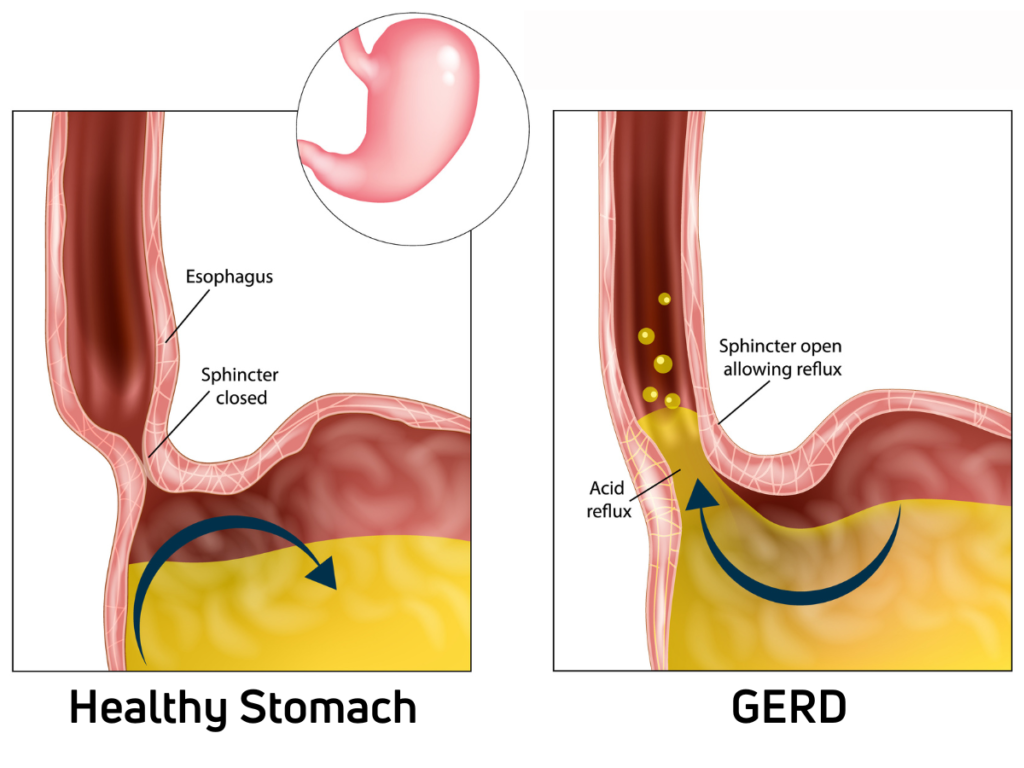

- Could Jerome be experiencing pain from something like gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that is causing agitation and a short temper?

- Could he be waking up at night because of reflux symptoms, and then, because of poor sleep, he is now agitated?

- Could there be a problem with constipation causing a chronic uneasy or painful feeling?

- Could he be experiencing medication side effects which include mood or mental changes like agitation and confusion?

It’s always worth evaluating for an underlying medical cause of any behavior change.

Behavior Discussion

As with all people, communication is a key component of our lived experience. The most desirable first action, as a behavior analyst, is for us to be able to observe, interact, and communicate with the people we work with. Jerome has an advantage, in some ways, in that he is a proficient expressive and receptive communicator. Although he may not always express himself in socially appropriate and preferred manners (i.e., with undesirable behavior), inviting Jerome to sit in a calm, quiet environment, away from peers and aversive stimuli, can be incredibly cathartic for him.

When meeting with people who are agitated but do not jeopardize their health and safety, it is important to model the behavior we wish for them to exhibit. This isn’t necessarily done formally, but sitting down, talking calmly and steadily, and finding a quiet area can significantly assist. Doing more listening than talking is also advisable, as well as providing affirming statements when possible and avoiding lecturing! Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, recurrent reminders of potential punishment rarely reduce agitation!

Utilizing effective communication strategies is valuable for assisting the agitated person and allows us to glean valuable insight from the person. Much of the information known about Jerome’s current status comes from him, but also from his willingness to sit and talk with a member of the interdisciplinary team. The interactions with Jerome aim not to punish or lecture him about his behavior but to understand the underlying issues and possible resolutions better.

Outcome

After meeting with the Behavior Analyst, Jerome’s behavioral characteristics and general psychobehavioral status were presented to the interdisciplinary team, including the psychiatrist, as him having a “short fuse,” sustained agitation over several days, “racing mind,” fidgety, “gross overreaction to benign occurrences,” and misperception of social and environmental events. The team agreed that an adjustment to the psychotropic medication regimen would be warranted, which was done slowly over three months. In the eight months since the last medication change, Jerome has shown no instances of aggression, had no contact with law enforcement, obtained competitive employment, and returned to routine basketball games at the local community center.

As service providers and interdisciplinary team members, we are responsible for ensuring the global health and well-being of the people we serve. Part of this responsibility includes recognizing that some people do benefit from the use of psychotropic medications. A healthy mind and body provide the foundational support that increases the quality of life of any person.

Author Bio:

Ley is a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst with an academic and professional background in gerontology and applied behavior analysis. Ley’s specialties include behavioral gerontology and the behavioral presentations of neurocognitive disorders, in addition to working with high-management behavioral needs for dually diagnosed persons with intellectual disabilities and mental illness. He is an officer on the Board of Directors for the National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices, works closely with national organizations such as the National Down Syndrome Society, and is the owner/operator of Crescent Behavioral Health Services based in Columbia, SC.

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and President of IntellectAbility. He has over 20 years of clinical experience providing medical care for people with IDD and complex medical and mental health conditions. He is the author of “Clinical Pearls in IDD Healthcare” and developer of the “Curriculum in IDD Healthcare,” an eLearning course used to train clinicians on the fundamentals of healthcare for people with IDD. He is also the host of the “IDD Health Matters” podcast.