Advancing Health Equity For People With Intellectual And Developmental Disabilities

By Dr. Craig Escudé | Oct. 20, 2022 | 7.5 Minute Read

As published on Health Affairs Forefront

There are numerous health inequities for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). They experience lower rates of preventive screening; higher rates of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease; lower life expectancy; and higher rates of pregnancy complications. If that’s not enough, they have been at nearly six times greater risk of dying from COVID-19.

What is driving these disparities?

There are a number of contributing factors, including unconscious bias against people with disabilities, physical access barriers, and inequities due to unmet social determinants of health, to name a few. But there is one area where health care policymakers and leaders can have an immediate impact for the 10 to 16 million people with IDD in the US. That is: by educating the health care workforce to meet the needs of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

I started practicing in this hidden and unknown field of medicine in the late 1990s. As medical director for a large, state-run program for people with IDD, I was put in charge of the health care of several hundred people with severe and profound levels of intellectual and developmental disabilities. At first, I thought, “No worries, it’s just like any other area of general practice.” But it was only a matter of a few days before I realized how ill-prepared I was, even as a board-certified family physician, to meet these individuals’ health care needs.

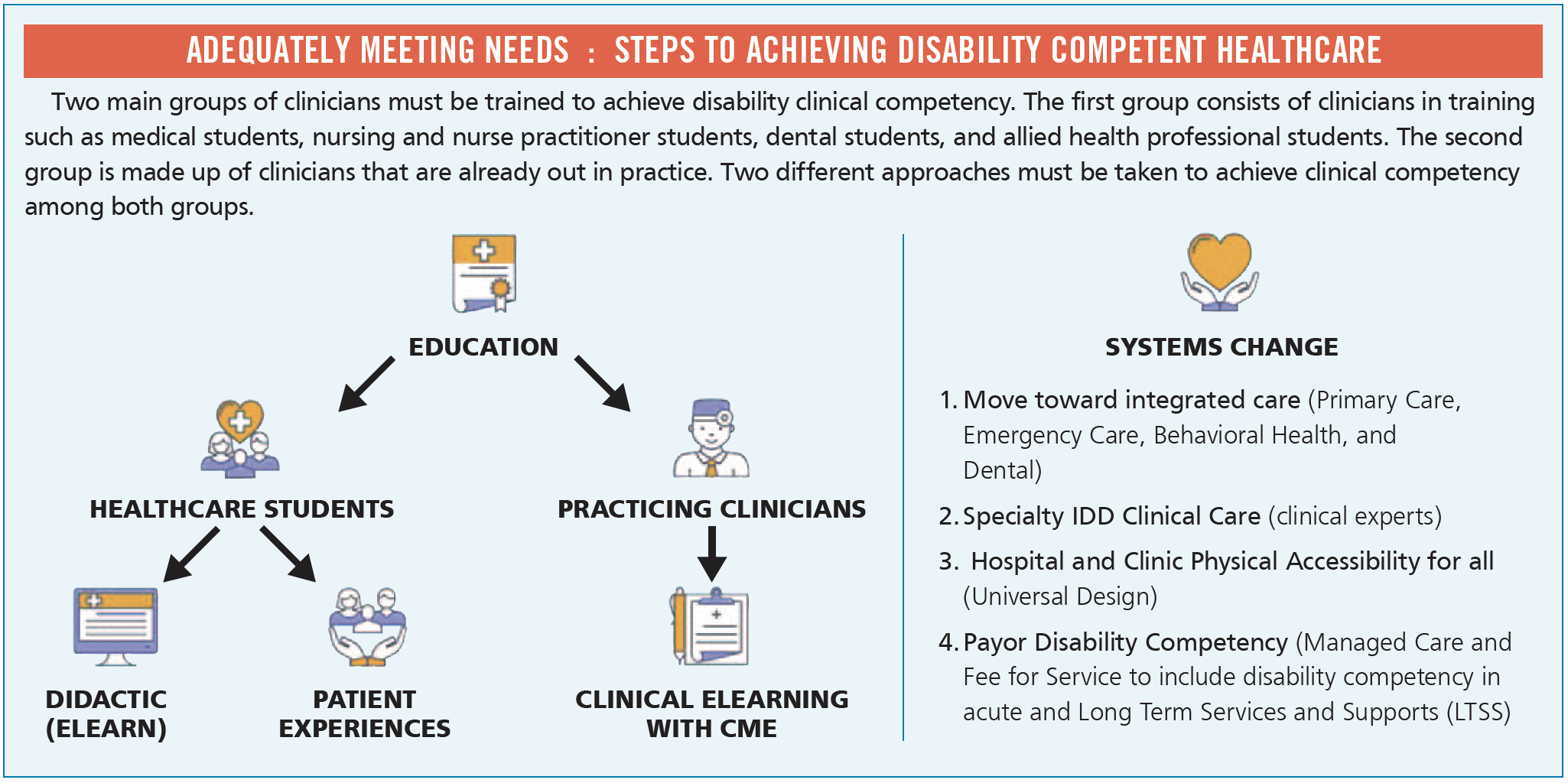

Educating physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, dentists, and other clinicians is paramount to reducing health inequities for people with IDD. And I’m not the only one saying this. According to the 2022 National Council on Disability’s Health Equity Framework for People with Disabilities, “comprehensive disability clinical-care curricula [should be required] in all US medical, nursing and other healthcare professional schools.”

Most clinicians are not taught the clinical diagnostic skills to accurately diagnose and develop treatment plans for people with IDD. Yes, most clinicians are trained to take care of many of the specific medical conditions that people with IDD may experience, such as aspiration pneumonia, bowel impaction, seizures, gastroesophageal reflux, and the like. But the greatest gap in training lies in teaching students how these conditions often have different presenting signs and symptoms in people with IDD.

Diagnostic Overshadowing

Michael is a 35-year-old man with a severe level of intellectual disability who lives in a group home. He begins to become aggressive throughout the day, wakes up at night yelling, finds various objects on the floor, and starts eating them. Initially, it is noted by his support staff that the aggression seems to occur at or just after mealtime, but after a few weeks, the behavior worsens and starts occurring before mealtimes and at bedtime. An untrained clinician might very easily attribute these changes to the fact that Michael has an intellectual disability, and “that is just what people with IDD do.” They might even recommend that he be started on a psychotropic medication or sleep aid due to the agitation, aggression, and insomnia.

Such circumstances are often described as “diagnostic overshadowing”—any situation in which a clinician reflexively attributes a person’s symptoms or behavior to their disability instead of looking for treatable underlying medical causes. It was the recent focus of a June 2022 Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert, which states that “individuals with disabilities are at greater risk of diagnostic overshadowing” and that “the potential of diagnostic overshadowing presents added risk to individuals with disabilities.”

How would Michael’s symptoms and behaviors be treated by someone educated and experienced in providing health care for people with IDD?

With the right training, a clinician would be far more likely to recognize that Michael may be agitated before and around mealtimes because he is experiencing pain associated with gastroesophageal reflux. He is waking up yelling at night because reflux symptoms often occur more frequently when a person is lying down. He is exhibiting pica behavior—that is, eating things that are not food—because every time he swallows, he washes the acid back down. A trained clinician would be far more likely to prescribe an acid-reducing medication to treat the underlying condition, instead of a psychotropic medication that would do nothing for the reflux and could likely make things worse.

To address diagnostic overshadowing, it is essential to educate clinicians about common presentations of treatable medical illness in people with IDD, medication management, and The Fatal Five conditions that are the top causes of preventable morbidity and mortality in people with IDD. In addition, education should highlight physical and nutritional supports, co-occurring mental illness, vitamin D deficiency, differences in dementia presentations, and other challenges that are unique to caring for people with IDD.

Looking Forward

Where do we go from here?

- First, policymakers must encourage local hospitals and clinicians’ offices to provide training on caring for people with IDD to their clinical staff.

- Second, medical schools, nursing schools, and other health professional training programs should incorporate mandatory disability-competent training for their students.

- Third, we must raise awareness among clinicians and health system leaders about IDD-related resources and training options for their staff through such associations as the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry, the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association, the Institute for Exceptional Care, and such resources as the Curriculum in IDD Healthcare.

- Fourth, legislators and medical societies should also promote or require education in this area.

- Finally, managed care organizations should also provide training to their health teams about this important aspect of health care.

With better education of the health care workforce, anyone, with or without a disability, will be able to present to any clinician’s office or hospital and receive at least a basic level of competent and compassionate health care—a good start toward health equity for all.

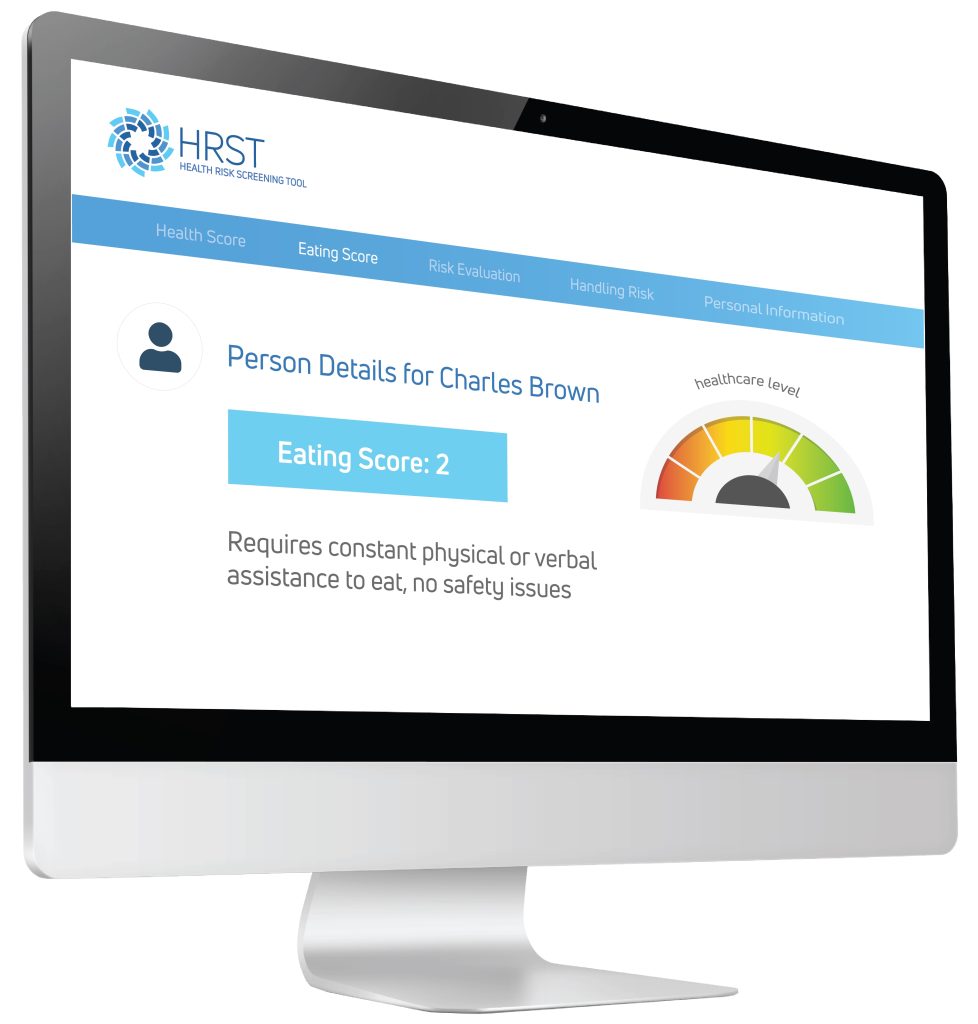

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of

The

The