Sepsis and Disability: The High Cost of a Preventable Medical Emergency

Sepsis and Disability: The High Cost of a Preventable Medical Emergency

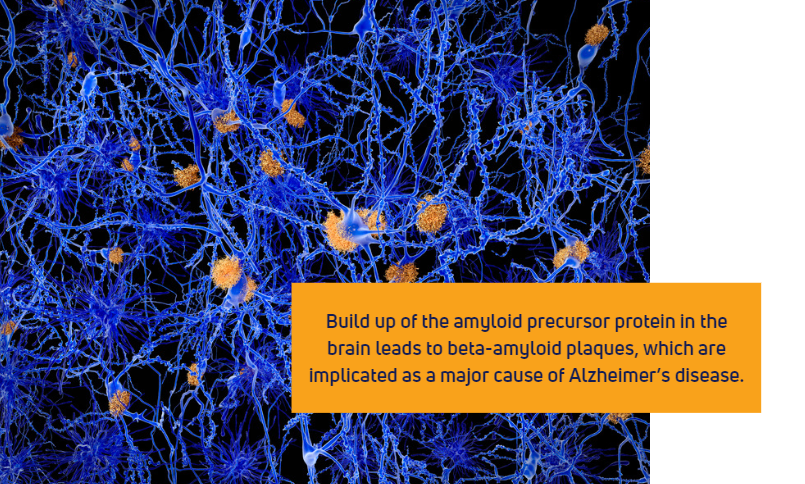

For people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD), even minor infections can quickly escalate into life-threatening emergencies. One of the most dangerous yet preventable conditions is sepsis—a severe reaction to an infection that can lead to organ failure, shock, and death if not treated promptly.

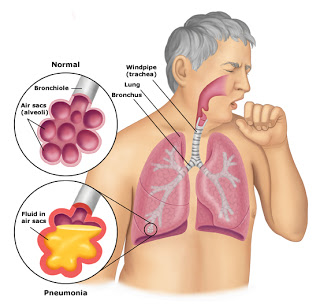

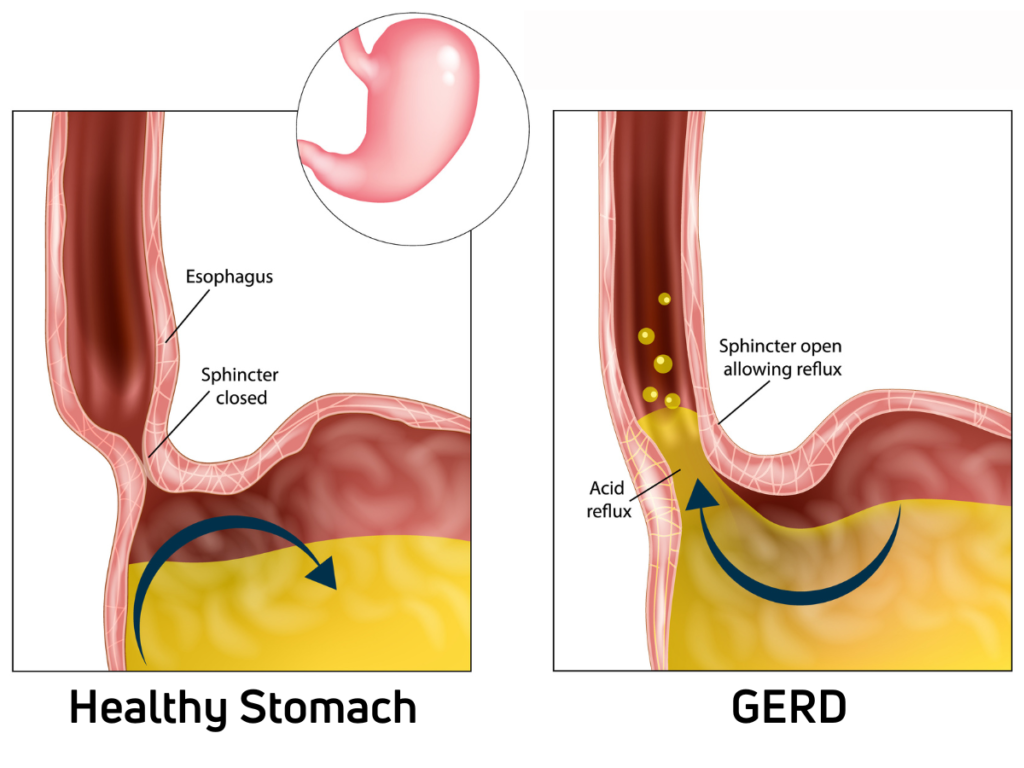

Sepsis typically develops from a common infection, such as a urinary tract infection (UTI), pneumonia, or an untreated wound. While early treatment can prevent severe complications, many people with disabilities struggle to communicate pain or discomfort, making it crucial for supporters to recognize early warning signs. However, a lack of awareness, understaffing, and delayed medical intervention often result in preventable hospitalizations, costly treatments, and tragic outcomes. The following case is based on real-life events.

Sophia’s Story: A Small Infection with Life-Threatening Consequences

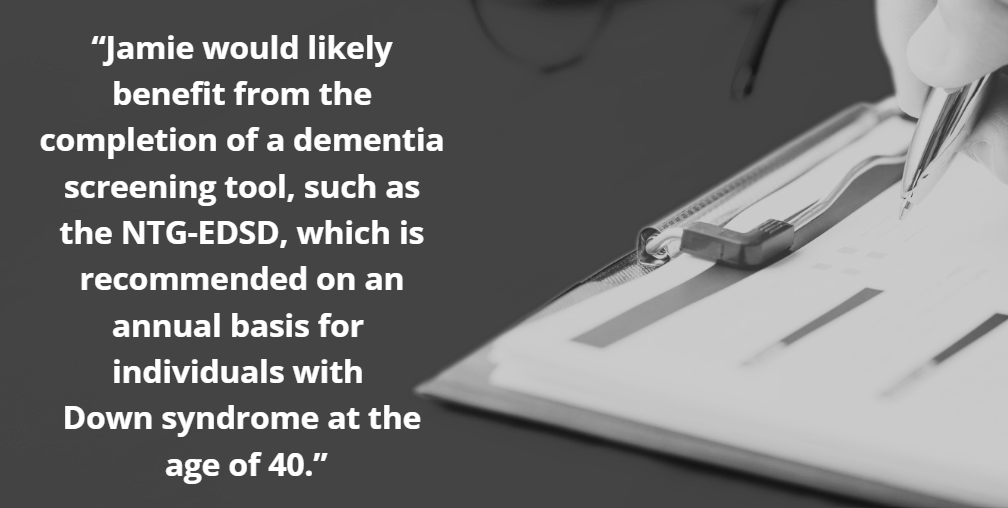

Sophia, a 38-year-old woman with autism and epilepsy, lived in a group home where supporters assisted her with daily needs. Due to sensory sensitivities and communication challenges, she had difficulty expressing discomfort, which made her vulnerable to undetected medical issues. She needed help with toileting hygiene and has a history of urinary tract infections (UTIs).

One afternoon, Sophia appeared more withdrawn than usual and refused to eat. Supporters noticed she was running a mild fever, but since she did not verbally complain of pain, they assumed she had a minor cold, gave her fluids, and recommended that she rest. What they didn’t realize was that Sophia had developed a urinary tract infection (UTI), which was rapidly spreading through her body.

Over the next 24 hours, her condition worsened—her fever spiked, her breathing became rapid, and she seemed increasingly confused. By the time emergency services were called, Sophia was in septic shock; her blood pressure had plummeted, and her organs were failing. She was rushed to the hospital and placed in intensive care, requiring IV antibiotics, IV fluids, and life support to stabilize her condition.

The Cost of Unrecognized Symptoms

Sophia remained in the intensive care unit (ICU) for two weeks and required an additional month in rehabilitation before she could return home. She experienced significant suffering and nearly lost her life. Additionally, the financial impact was devastating:

- Hospital and ICU care exceeded $250,000.

- Dialysis treatments for kidney complications added another $120,000.

- Rehabilitation and follow-up medical care costed tens of thousands more.

What makes this situation even more tragic is that it was entirely preventable. Had Sophia’s infection been identified and treated when the first symptoms appeared, she could have recovered with a short course of antibiotics—avoiding the physical suffering, emotional distress, and financial burden that came with her hospitalization

How IntellectAbility’s Tools and Training Impact Outcomes

Sepsis progresses rapidly, but early detection and proper medical care can prevent it from becoming life-threatening. IntellectAbility’s Health Risk Screening Tool (HRST®) and eLearning training programs are designed to catch warning signs early and ensure people with disabilities receive the proper care before a crisis occurs.

- Health Risk Screening Tool (HRST): Identifying Sepsis Risks Before It’s Too Late.

The HRST is a scientifically validated tool that helps identify health risks before they escalate into emergencies. When Sophia’s Supporters use this tool:

- They will recognize that her communication difficulties and history of infections put her at a higher risk for sepsis.

- A care plan can be put in place to monitor for signs of infection—such as fever, fatigue, or changes in behavior.

- Supporters can be trained to seek immediate medical attention at the first signs of sepsis, preventing its progression to a life-threatening condition.

2. Supporter Education: Recognizing the Early Signs of Sepsis

Many supporters are not fully trained to identify the subtle warning signs of infections or sepsis, leading to delays in treatment. IntellectAbility’s training programs empower supporters with the knowledge to:

- Recognize that changes in behavior, appetite, or energy levels can be early signs of infection.

- Understand that symptoms like fever, rapid breathing, and confusion are medical emergencies—not minor issues.

- Take immediate action by seeking medical care before an infection progresses into full-blown sepsis.

3. A Proactive, Person-Centered Approach to Healthcare

IntellectAbility promotes a proactive, person-centered approach that focuses on preventing medical crises rather than reacting to them. With routine health risk screenings, properly trained supporters, and early intervention, unnecessary hospitalizations and life-threatening emergencies like Sophia’s can often be avoided.

Why Are Preventable Cases of Sepsis Still Happening?

Sophia’s story is not unique. Many people with disabilities suffer from preventable medical crises because of:

- Delays in recognizing symptoms due to communication challenges

- Supporters not being trained to detect subtle warning signs

- Lack of proactive healthcare planning

Sepsis is one of the leading causes of preventable death in people with disabilities, yet simple, low-cost interventions could dramatically reduce its occurrence.

The Solution: Prioritizing Prevention Over Crisis Response

Sophia’s hospitalization—and the overwhelming costs associated with it—could have been avoided with proactive healthcare strategies, supporter education, and early intervention.

Using health risk screening tools and supporter training programs leads to:

- Earlier detection of infections, reducing hospitalizations

- Better-trained supporters who can confidently recognize medical red flags

- Lower overall healthcare costs due to fewer emergency interventions

Sepsis should never reach the point of being life-threatening, yet cases like Sophia’s continue to occur because early warning signs are missed, and treatment is delayed. With the right tools, training, and awareness, these preventable medical crises can be stopped before they begin.

By integrating IntellectAbility’s low-cost, high-value Health Risk Screening Tool and specialized training programs, we can ensure that people with disabilities receive the timely, high-quality care they deserve—reducing preventable deaths, improving quality of life, and easing the financial burden on families and healthcare systems.

The choice is clear: invest in prevention today or face the high cost of delayed action tomorrow

Take the Fatal out of the Fatal Five

License health and safety training eLearns for your entire organization.

Contact us today to receive

a free preview and custom price quote.