By Craig Escudé, MD, FAAFP, FAADM

Have you ever accompanied someone with an intellectual disability to a medical appointment due to a new, concerning behavior, only to be told by the clinician that they are doing this just because of their disability? That’s diagnostic overshadowing- a term that describes when clinicians attribute a new or untoward behavior to the fact that the person has an intellectual disability rather than looking for some underlying medical or environmental cause. And it is all too common in the medical profession. Why? The primary reason is the lack of training of clinicians to adequately meet the healthcare needs of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD).

The National Council on Disability released the Health Equity Framework for People with Disabilities in February of 2022. In it, the Council calls for 4 main changes that are needed to improve healthcare for people with disabilities, including those with IDD:

- Designating people with disabilities as a Special Medically Underserved Population (SMUP) under the Public Health Services Act

- Requiring comprehensive disability clinical-care curricula in all US medical, nursing, and other healthcare professional schools and require disability competency education and training of medical, nursing, and other healthcare professionals

- Requiring the use of accessible medical and diagnostic equipment

- Improving data collection concerning healthcare for people with disabilities across the lifespan

All four, along with the thirty-five additional recommendations in the document are important to achieve health equity for people with disabilities, but let’s talk about number two in more detail.

Disability Competency versus Clinical Competency

Becoming disability competent should be a requirement of every clinician, hospital, and healthcare payor entity including health maintenance organizations and fee for service payors. But, for clinicians, disability competency is not enough. A simple definition of disability competency is where the basic premises of the world of people with IDD is understood. Examples might include understanding different ways a person may communicate, appreciating the network of support upon which many people with disabilities rely, and understanding the necessity of creating physical environments where people with disabilities have equal access with the availability of scales that can weigh people in wheelchairs, exam tables that can move to lower positions to allow access, and the like. But healthcare providers must go beyond this level of understanding to attain true disability clinical competency. They must acquire the clinical and diagnostic skills that foster the provision of competent healthcare to people with IDD.

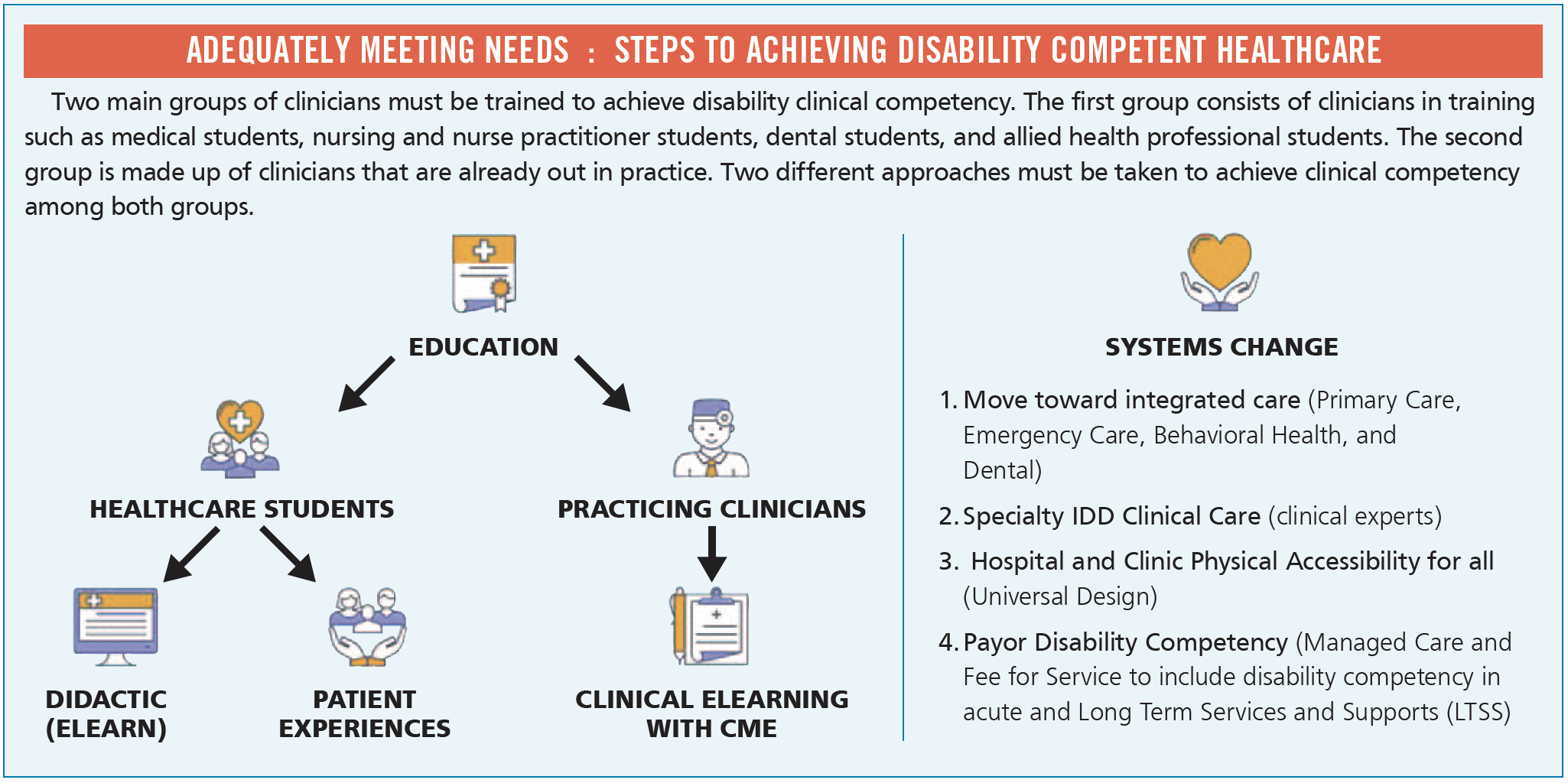

Two main groups of clinicians must be trained to achieve disability clinical competency. The first group consists of clinicians in training such as medical students, nursing and nurse practitioner students, dental students, and allied health professional students. The second group is made up of clinicians that are already out in practice. Two different approaches must be taken to achieve clinical competency among both groups.

Healthcare Professional Students

IDD healthcare curricula must be incorporated into every clinical training program in the US and abroad. There are two main components to achieving clinical competency: didactic education and hands-on clinical experience.

Didactic instruction should focus on teaching information such as what behaviors might be pointing to specific, treatable underlying medical or dental conditions in a person who does not uses words to communicate, the steps to take to evaluate the cause of newfound aggressive behavior in a person with IDD, the most common causes of preventable illness and death in people with IDD, and other clinical and diagnostic lessons.

Didactic training should be accompanied by experiential training where students interact with people with disabilities on different levels to gain insight into and appreciation of the lives of people with IDD. Standardized patient scenarios and real-life clinical experiences will help develop the skillsets needed to provide appropriate clinical assessments and medical treatments to people with IDD.

One of the challenges to teaching these skills is the limited number of currently available experts in this field to teach these courses. If every medical, nursing and allied health professional training program in the US wanted to employ clinicians with the expertise to teach this information in their schools, they would have a difficult time finding qualified clinicians to do so. Fortunately, with advances in eLearning courses, this type of information is more readily available than ever before. In a matter of days, a school could bring an IDD expert to their students through eLearning.

Practicing Clinicians

Society cannot wait until every school implements IDD training, all of their students graduate, and then replace every practicing clinician to attain a disability clinically competent workforce. Healthcare providers who have completed their training and are out in practice also must be trained to improve the availability of IDD competent healthcare providers. The challenges here are a bit different. Many clinicians are not aware of their own need to develop clinical competency in this area. It’s similar to the old saying, “we don’t know what we don’t know.” However, once they begin to gain some insight into this world, it becomes clear that additional information and skills about IDD healthcare would be of great benefit to all patients in their practices with vulnerabilities including people who are aging, those with dementia, people with traumatic brain injury and others. But how do we get this information to practicing clinicians who are busy with, well, practicing?

To do this, the information must be concise, practical, and afford an opportunity to fulfill continuing medical and nursing education requirements. Adding “teeth” in the form of this type of training being required by their professional accreditation academies or state licensing boards would also provide incentives. Again, one of the best ways to deliver this type of training is through online eLearning courses. They are efficient and can be done on the clinicians’ own time and at their own pace.

In recent years, there has been an increase in focus being placed by different organizations to increase clinical competency among healthcare providers. The American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD.org) has fostered the National Curriculum Initiative in Developmental Medicine which has cultivated the implementation of varying degrees of training in over 20 medical schools. The Developmental Disabilities Nurse Association (DDNA.org) credentials nurses to provide healthcare for people with IDD. The Institute for Exceptional Care (ie-care.org) is working to improve access to competent healthcare for people with IDD addressing both educational as well as the payor components needed to achieve this goal. IntellectAbility (ReplacingRisk.com) is a company that focuses on health risk identification and prevention as well as training of all levels of supporters and has eLearn courses specifically geared to teaching physicians and nurses about IDD healthcare. One particular course, the Curriculum in IDD Healthcare, is used in medical and nurse practitioner schools as well as by practicing clinicians and has demonstrated efficacy in improving clinical confidence in IDD healthcare for both students and practicing clinicians.

Non-clinician supporters

What can non-clinicians do to improve IDD clinical competency? Here are a few thoughts: Educate healthcare providers about organizations and options to receive IDD clinical training. Work with medical licensure boards and specialty organizations to encourage or require IDD clinical training. Encourage and support health professional schools to incorporate IDD training into their curricula. And reach out to payors to encourage them to work to adjust payments to help foster better healthcare provision for people with disabilities.

With the increase in interest in this area and continued movement toward improving training opportunities for students and practicing clinicians, we will come to a place where anyone with any level of disability will be able to present to any clinician’s office or hospital and receive a basic level of compassionate and competent healthcare. Let’s work to make this sooner rather than later.

About the author:

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of IntellectAbility. He has more than 20 years of clinical experience providing medical care for people with IDD and complex medical and mental health conditions serving as medical director of Hudspeth Regional Center in Mississippi for most of that time. While there, he founded DETECT, the Developmental Evaluation, Training, and Educational Consultative Team of Mississippi. He is the author of “Clinical Pearls in IDD Healthcare” and developer of the “Curriculum in IDD Healthcare”, an eLearning course used to train clinicians on the fundamentals of healthcare for people with IDD.

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of IntellectAbility. He has more than 20 years of clinical experience providing medical care for people with IDD and complex medical and mental health conditions serving as medical director of Hudspeth Regional Center in Mississippi for most of that time. While there, he founded DETECT, the Developmental Evaluation, Training, and Educational Consultative Team of Mississippi. He is the author of “Clinical Pearls in IDD Healthcare” and developer of the “Curriculum in IDD Healthcare”, an eLearning course used to train clinicians on the fundamentals of healthcare for people with IDD.