Missed Diagnosis: How Many Times Have You Seen This Happen?

Jerome is 22 years old. He enjoys NASCAR racing, going to the beach, and eating out at restaurants. He works 12 hours per week at a local grocery store and, in his leisure time, likes to watch sports on TV with his dad and brothers. Jerome uses a wheelchair and requires assistance with activities of daily living, including eating, dressing, and bathing. He communicates primarily through gestures, facial expressions, noises, and pictures, using the basic communication device he received in high school. He lives at home with his parents, who are his primary caregivers. He also receives personal care and employment support during the day from a paid supporter named Cecelia.

Cecelia recently approached Jerome’s mother because she has been noticing changes in his behavior over the past several months. Typically upbeat, Jerome has been frowning more and is less interested in activities that used to make him happy. Last week, when asked if he wanted to stop at a local café for lunch, he shook his head to indicate “no,” yelled, and banged his wheelchair. And this week, Jerome used his communication device to indicate “sick” and “stay home” on a workday-something he had never done before.

Jerome’s mother was also seeing subtle changes in Jerome that were concerning. She shared with Cecelia that Jerome was groaning a lot, not sleeping well at night, and seemed to be eating less than usual at mealtimes. He recently yelled at his brother and purposely knocked a bowl of snacks on the floor while getting ready to watch the Sunday afternoon football game- something he usually loves to do. He had also started chewing on his hands, causing chafing and redness.

When asked about how he was feeling, Jerome dropped his head, grimaced, looked away, and, using his communication device, indicated he felt “sick,” “tired,” and “mad.”

Jerome’s mother scheduled an appointment with his primary care provider. Unfortunately, this appointment did not go well all around. The provider was new to the practice, as was Jerome, having recently transitioned from his long-time pediatric provider. Jerome and his mother waited for almost an hour past their scheduled appointment time, and when the provider came into the room, she did not acknowledge Jerome, speaking only to his

mother. A cursory exam was done at the same time Jerome’s mother was filling the provider in about his recent behavioral changes and his complaints of feeling sick and mad. In less than 15 minutes, the provider concluded that Jerome was “probably depressed given his situation” and recommended that Jerome be started on tricyclic anti-depressant medication.

In the meantime, Cecelia contacted Jerome’s case manager to inform her of her discussion with Jerome’s mom and to let her know the outcome of his appointment with his primary care provider. The case manager, who was also relatively new to Jerome, thanked Cecelia for the information. Recognizing that Jerome’s symptoms represented a change in health status, she accessed his web-based Health Risk Screening Tool (HRST) record and updated it accordingly.

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Using the information provided by the case manager, the HRST recognized the possibility of an undiagnosed gastrointestinal condition as the potential cause of Jerome’s behavioral symptoms and produced a “service consideration” suggesting the need for clinical follow-up to rule out Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (more commonly known as GERD).

Meanwhile, Jerome was taking his anti-depressant but wasn’t feeling any better. His behavior continued to deteriorate; he lost 12 pounds and called in sick to work so often that he was in danger of losing his job. He was exhausted from lack of sleep, as were his parents.

The case manager called Jerome’s mother to share the service consideration produced by the HRST and assisted her with obtaining a referral to see a gastroenterologist. As luck would have it, the gastroenterologist had a brother with disabilities, was happy to meet and talk with Jerome and his mother, and quickly recognized that Jerome’s “behaviors” were probably related to acid reflux which can cause pain and discomfort at mealtimes and is exacerbated when lying down in bed. Diagnostics were completed, and a diagnosis of GERD was made.

Jerome’s diet was adjusted, and his bed was positioned so that the head of the bed was higher than the foot of the bed. Medications, including antacids and H-2 (histamine) blockers, were ordered. Jerome’s primary care physician was consulted, and the tricyclic anti-depressant was discontinued because a diagnosis of depression no longer seemed appropriate and because this class of medications is to be avoided in people with GERD because it can actually worsen their symptoms.

Within two weeks, Jerome was back to his baseline, smiling, eating, working, and watching the NASCAR races with his brothers.

What happened in this situation?

Jerome was likely the victim of “diagnostic overshadowing,” a phenomenon that stems from cognitive bias and poses a serious health risk for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). Often, symptoms that would otherwise be addressed through immediate medical evaluation are discounted and attributed to the person’s IDD. No further assessment is conducted, differential diagnoses are not considered, and medical conditions continue untreated, often while psychotropic medications are being given to “treat” the person’s symptoms. This bias is usually unconscious and can be addressed through healthcare provider education.

Fortunately, Jerome has attentive and knowledgeable caregivers and advocates who understand the importance of “looking beyond the symptoms,” access to a robust health risk management tool, and a disability-competent health care provider. However, there are many others who do not. In order to ensure health equity for all people with IDD, there is a need to:

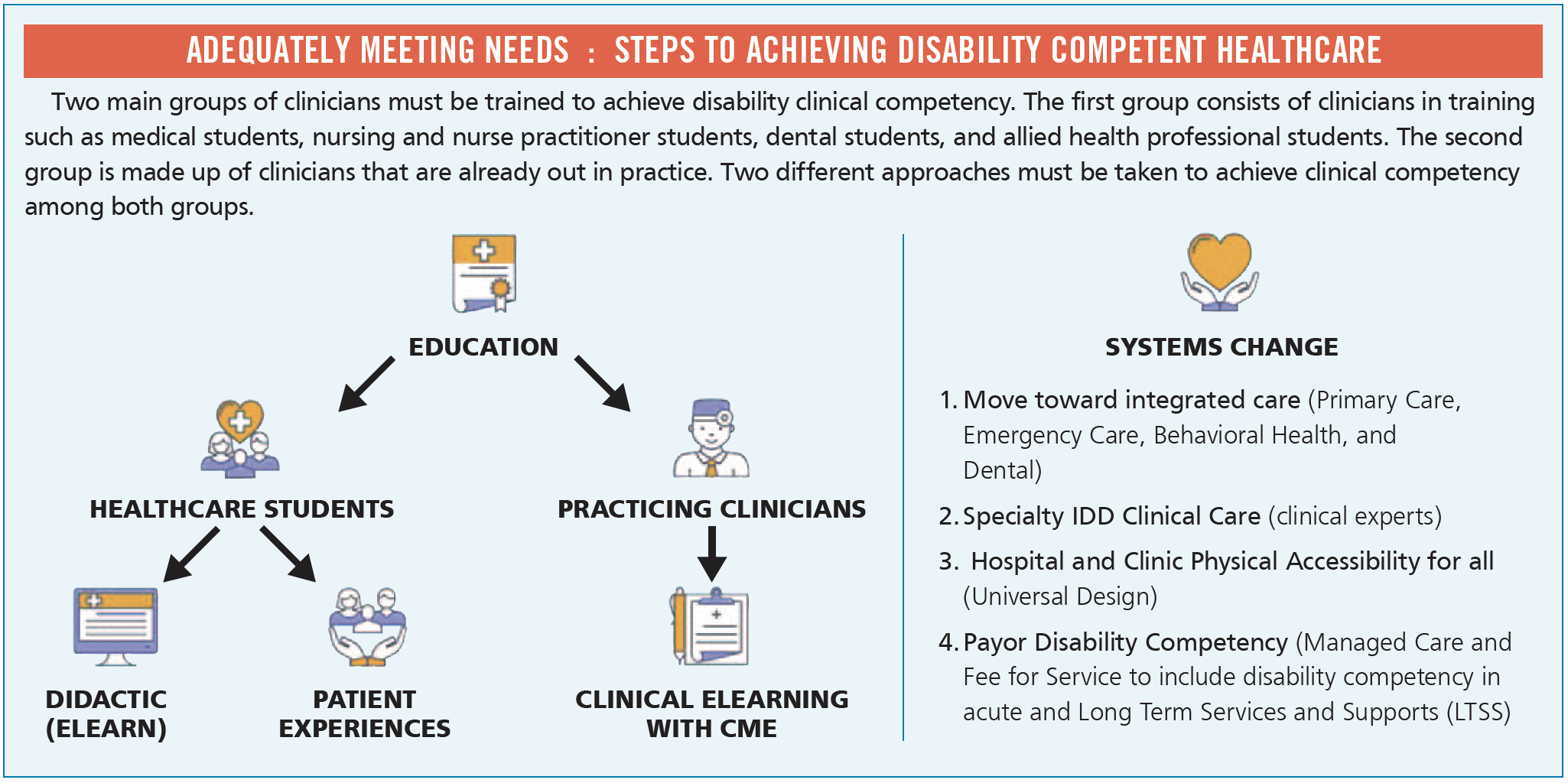

- Ensure health care providers receive education to ensure they are disability healthcare competent

- Effectively monitor, identify, and address emerging health risks

- Educate support staff to recognize and report symptoms of the “Fatal Five Plus,” conditions most likely to lead to morbidity and mortality for people with IDD: aspiration, constipation, dehydration, seizures, sepsis, and GERD

IntellectAbility can help. Contact us for more information about the Health Risk Screening Tool (HRST), the Curriculum in IDD Healthcare, and our eLearn course on the Fatal Five.

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of

Dr. Craig Escudé is a board-certified Fellow of the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and is the President of